Some Thoughts Towards a Theory of

Musical Ekphrasis

Siglind Bruhn

1 Art about Art?

|

"...il y a de bizarre, et même

d'inquiétant, dans le fait d'une inspiration de seconde main,

cherchée dans les oeuvres d'autrui, et cherchée dans un

art dont les buts et les moyens sont très différents de

ceux qui charact‚risent l'art poétique. Est-ce vraiment

légitime? Est-ce vraiment utile et fécond?"

[Étienne Souriau, La poésie française et la

peinture (London 1966), p. 6]

|

|

"...there is something odd, and even disturbing, in

second-hand inspiration, sought in the works of someone else, and

sought in an art form of which the aims and the means are very

different from that which characterize poetry. Is this really

legitimate? Is this truly useful and fruitful?"

|

There are various ways in which one art form

can fruitfully relate

to another. Coexistence is much more frequent--and apparently much

less disturbing for an audience--than the declared attempt at a

"transformation" or new representation in another sign system. Does

this "second-hand inspiration," as Souriau called it, constitute a

genuine creative act? To overemphasize what seems to be his question:

is there a risk that the "representation of a representation" might

suck the blood and life force from the first work, or to come out as

a merely derivative, bloodless response? What do artists mean when

they say that the new work can be cherished alone but fully

understood and appreciated only in light of the earlier work on which

it reflects?

When composing his piano cycle Gaspard

de la nuit, Ravel

not only chose for his three pieces the titles of three of Bertrand's

poems, but actually reprinted each poem on the page facing the

beginning of the musical piece that refers to it. While Ravel's music

is no doubt beautiful and self-sufficient when appreciated without

knowledge of the literary source (as is usually the case in today's

concert practice), the listeners' insight into the depth of the

musical message increases dramatically once the music is comprehended

in light of the poem.

Let me briefly recall the central piece, Gibet.

Bertrand,

in asking us to witness the death of a hanged man, draws our

attention to two facets of a transitional space. On the one hand,

there is the very moment between life and death; the two framing

verses clearly stake out this ground. The question that pervades all

six stanzas of his poem asks after the origin and nature of a

sound--a sound that, after having been suspected to come from the man

himself or from the insects that surround his head, turns out to be

the tolling of the death-knell. At the beginning, the lyrical "I" is

wondering whether the sound may be the sigh of the hanged man; there

may still be life. But the end speaks unequivocally of a carcass, a

corpse. The entire poem can thus be read as an unfolding of that

moment between almost-no-life and definite death. On the other hand,

Bertrand elicits, in the four central stanzas, the interaction

between the living and the not-quite-dead. Significantly, the

creatures proposed as possible sources of the puzzling sound are not

animals whom a man could look in the eye, but

insects--representatives of transition. Cricket, fly, beetle, and

spider all relate to the hanged man in ways that evolve from the

innocuously disinterested to the downright morose.

Ravel captures many of the nuances expressed

through Bertrand's

poem in his piano piece. As in the poem, the tolling of the bell is

the unifying feature. The tolling never pauses and never changes its

pitch. Its rhythm, however, makes it clear that all is not in order

here. Against this incessant sounding of the death-knell, Ravel

proceeds to lay out his melodic material which, in four ever more

emotionally loaded steps, moves further and further away from any

meaningful relationship to the central scene and the dignity we

expect in the context of a death-knell. In the image drawn by

Bertrand, this musical development corresponds with the increasingly

disrespectful way in which the creatures of transitional space relate

to the hanged man. While Ravel's piano piece is undoubtedly beautiful

when heard as absolute music without any connection to an

extra-musical stimulus, the listener gains access to its full depth

only when appreciating it as a transmedialization of Bertrand's

poem.

2 Musical Ekphrasis in Intermedial

Space

As the brief description shows, Ravel's

piano cycle on Bertrand's

poems in no way constitutes vaguely impressionistic "program music."

Instead, this is a case of a transformation of a message--in content

and form, imagery and suggested symbolic signification--from one

medium into another. For this phenomenon we seem to lack a specific

term; I will make a case for calling it "the musical equivalent to

ekphrasis." Not surprisingly given the lack of a distinctive term, no

methodology seems to have been developed that would allow us to

differentiate within what I will argue is a unified and highly

sophisticated genre, or to define the genre within the larger fields

in which it is situated.

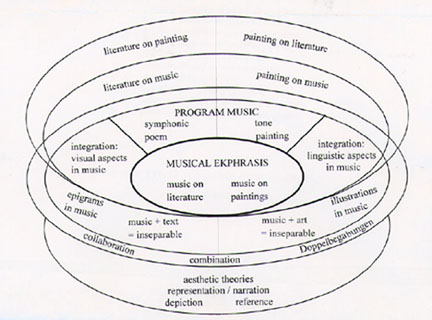

These fields can be imagined as surrounding

musical ekphrasis,

linked to it at various points of interaction or by way of the

questions asked in aesthetic theory about assumptions underlying all

of them. (In the graphic overview I single out two of music's sister

arts--painting and literature--to stand for what is of course a much

richer texture of interactions, encompassing not only other forms of

visual art but also dance and mime as well as many hybrid forms of

artistic expression. By the same token, the aesthetic theories that

question musical ekphrasis with regard to its concepts, touch on many

more issues than the few that I have listed in the diagram.)

Among the possible pairings between two art

forms that express

themselves in different sign systems (verbal, pictorial, sonic,

kinetic, etc.), the relationship between words and images is the one

that is most widely explored. And in fact, the most securely

established terminology is found in a field that has experienced a

significant revival in recent years: ekphrasis or, more

particularly, ekphrastic poetry: poems inspired by paintings or other

works of visual art, including etchings and drawings, sculptures and

architecture, photographs, films, etc. The field is amazingly broad

and varied both historically and geographically. In his three-volume

study Das Bildgedicht, the German scholar of ekphrasis,

Gisbert Kranz, lists 5764 authors of ekphrastic poetry representing

thirty-five languages and twenty-eight centuries (from Homer to our

days)! Altogether fifty thousand poems on visual art are referenced

in his 1500-page bibliography. James Heffernan in his seminal book of

1993, Museum of Words: The Poetics of Ekphrasis from Homer to

Ashbery, defines ekphrasis as "the verbal representation of

visual representation"; Claus Clüver, in his 1997 article

"Ekphrasis Reconsidered: On Verbal Representations of Non-Verbal

Texts," expands the definition fortuitously to "the verbal

representation of a real or fictitious text composed in a non-verbal

sign system."(FN1)

The musical equivalent of ekphrasis

is a much more recent

phenomenon. Moreover, the first examples of the budding new genre,

written in the last years of the 19th century, were mostly not

distinguished from the broader category of "program music."; Musical

compositions with explicit reference--whether verbal in titles and

accompanying notes or onomatopoeic--have existed for much of the

history of Western music; yet, I claim, musical ekphrasis has

not.

3 Musical Ekphrasis versus Program Music

This brings me to an important task in

approaching the subject

matter of this study, that of defining the criteria along which we

can agree to distinguish between musical ekphrasis on the one hand

and what is generally known as "program music" on the other. The two

genres belong to the same general species: both denote purely

instrumental music that has its raison d'être in a

definite literary or pictorial scheme; both have variously been

described as "illustrative" or "representative" music.While the term

"program music" is considered by many to be simply the umbrella term

for both kinds, I will argue that it is not only meaningful, but

essential for a full understanding of music of the "ekphrastic" kind

to attempt a distinction.

In literature, the equivalent is the

distinction between ekphrasis

proper and "word painting" or "Beschreibungsliteratur." One way of

approaching the difference is to ask whose fictional reality is being

represented. "Program music" narrates or paints, suggests or

represents scenes or stories (and, by extension, events or

characters) that may or may not exist out there but enter the music

from the composer's mind. The range of application for the term

"program music" is wide, spanning from the biographical (Strauss's

Aus Italien) and the emotional expression associated

with

nature near or far (from Beethoven's "Erwachen heiterer Gefühle

bei der Ankunft auf dem Lande" in the Pastoral Symphony to

Holst's The Planets) through the depiction of an historical or

literary character (Berlioz's King Lear, Liszt's Hamlet) all

the way to a musical impression of a philosophically created "world"

(Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra).

The musical equivalent to ekphrasis, by

contrast, narrates or

paints a fictional reality created by an artist other than the

composer of the music: a painter or a poet. Also, ekphrastic

music usually relates not only to the content of the poetically or

pictorially conveyed fictional reality, but also to the form and

style of representation in which this content was cast in its primary

medium.

The generous grouping and lack of

distinction between program

music and musical ekphrasis affected composers as well as listeners

and scholars. Composers, particularly at the beginning of the 20th

century when "program music" was gaining a bad reputation in

comparison to "absolute" or "pure" music, often obfuscated their full

intent in the hope to be taken seriously. Such concealment happened

not only with programs of the more general kind (one is reminded of

Mahler's withdrawing his poetic outlines for his symphonies), but

also and particularly in the case of music based on extant works of

art. Thus Schoenberg originally denied that his Pelleas und

Melisande was more than only vaguely inspired by the topic of

Maeterlinck's Symbolist drama, acknowledging only decades later how

exact a "transformation"; he had actually tried to achieve here. The

fact that listeners and scholars were discouraged from making a

distinction between the two adjacent categories of music resulted in

a considerable delay between the first occurrence of the phenomenon

of musical ekphrasis and its proper recognition.

I am interested in finding an answer to the

question what it may

mean if composers claim to be inspired by a poem or painting, a drama

or sculpture, and to have transformed the essence of that art work's

features and message, including their personal reaction to it, into

their own medium: the musical language. I expect to find as many

responses to the challenge of interartistic transformation as there

are works in the genre. Thus, while my investigations will be guided

by the search for a methodological framework within which all such

transpositions find their place, I admit that my fascination with the

variety of approaches taken and solutions developed overrides my

interest in the grid on which I may eventually lay them out.

4 Attempt at an Analog Definition

When pursuing the above-mentioned question

what exactly we mean

when we talk about a transmedialization of a work of literature or

art into music, I begin with the assumption that the creative process

that applies in the step from a painting to its poetic rendering can

usefully be compared to that which leads from a poem or painting to

its rendering in music; in fact I maintain that they correspond to a

degree that justifies adapting the terminology developed in the

adjacent field.

In view of this wider application, I would

thus like to offer a

third definition of ekphrasis which further generalizes Claus

Clüver's wording. Ekphrasis in this wider sense would then be

defined as "a representation in one medium of a real or fictitious

text composed in another medium." As I understand it, what must be

present in every case of ekphrasis is a three-tiered structure of

reality and its artistic transformation:

|

(1)

|

a scene or story--fictitious or real,

|

|

(2)

|

a representation of that scene or story in visual form

(a painting or drawing, photograph, carving, or sculpture (or, for that

matter, in film or dance;(FN2) in any mode that reaches us primarily

through our visual perception), and

|

|

(3)

|

a rendering of that representation in poetic language.

|

The poetic rendering can and should do more

than merely describe

the visual image. Characteristically, it evokes interpretations or

additional layers of meaning, changes the viewers' focus, or guides

our eyes towards details and contexts we might otherwise overlook.

Correspondingly, what must be present in every case of what I will

refer to as "the musical equivalent to ekphrasis" is

|

(1)

|

a scene or story--fictitious or real,

|

|

(2)

|

its representation in a visual or a verbal text, and

|

|

(3)

|

a rendering of that representation in musical language.

|

5 Depiction and Reference

Expanding from here, I wish to argue that

what and how music

communicates about any extra-musical stimulus falls into two

categories that can be seen as analogous with those pertinent in the

context of painting and poetry, namely, depiction and reference. I

will use depiction by musical means as encompassing not only

instances of mimicry, but also, and more importantly, emotions and

feelings. Correspondingly, reference by musical means, just like

reference by verbal and pictorial means, will be understood as

relying on cultural and historical conventions. In this context,

Leonard Meyer speaks of connotations, which he defines as "those

associations which are shared in common by a group of individuals

within a culture." Thus, he continues, "[c]onnotations are

the result of the associations made between some aspect of the

musical organization and extramusical experience."(FN3)

In music, a representation of "the extant

world" is not quite so

obvious. Schopenhauer objects fervently to the notion of musical

imitations of "phenomena of the world of perception,"(FN4)

and Tovey concurs with so many musicologists of his time who maintain

that programmatic elements in "serious" music are irrelevant to its

value as music.(FN5) One believes that music

has only very limited mimetic potential, while the other declares any

musical representation as undesirable. This was not always the

dominant view. Rousseau when writing his Dictionnaire de

musique in the 18th century clearly did not think so. Under the

heading "imitation" he included two entries, apparently conflating

"mimesis" and "imitatio." The second entry deals with the expected,

technical device of "the same aire, or one similar, in many parts,"

while the more prominent first entry explores the field of music

imitating things extra-musical, clearly arguing that this art is no

less capable of emulation than its sister arts.

Conventions established between the parties

engaging in

communication through representation need not, and in fact do not,

end with verbal language. The musical language--our primary concern

in this study--has developed a highly sophisticated catalogue of

signifiers that are agreed, within our cultural tradition, to be

understood as "pointing towards" non-musical objects. Among the most

well-known are

|

(1)

|

the semantic interpretation of brief musical units its

representation in a visual or a verbal text, and as "gestures" on the

basis of their kinesthetic shape,(FN6)

|

|

(2)

|

the figures of musical rhetoric developed in the 15th

and 16th centuries,

|

|

(3)

|

the retracing of a visual object (like the Cross) in

the pitch outline, and

|

|

(4)

|

the letter-name representation of or allusion to

persons--from Bach's famous pitch signature and those of Schumann,

Shostakovich,(FN7) Schoenberg, Berg, Webern,

etc. to the acrostic bows of reverence to a patron (Schumann's ABEGG)

or a lover (Berg's HF).

|

These four basic categories actually

constitute intrinsically

different ways of music's "referring to" a non-musical object.

Rhetorical figures, while modeled after (verbal) oratory, do not rely

on a mediator to be understood by those familiar with them; they

function almost like a semantic vocabulary. Gestures need

Einfühlung on the part of the individual listener,

who

perceptively links a certain structure with a kinesthetic image to

arrive at an affective connotation. Suggestive pitch contours are

(usually clumsy) translations of visual silhouettes and represent an

object only insofar as the listener attaches the (metaphoric)

concepts of "high" and "low" to what is heard as faster or slower

vibration;(FN8) and letter-name allusions

rely on the prior translation of the musically received message into

its notational equivalent and its basically arbitrary, though

conventionally prescribed alphabetic signifiers in order to be

decodable.

Yet even the latter two cases of mediated

representation can turn

into convention. The listeners' experience of a correlation between

certain musical tropes and implied meanings develops from unexpected

recognition--or the recognition of unexpectedness(FN9)

--via repeated exposure to anticipation, thus establishing a set of

conventions that may gradually come to bypass the original mediator,

even develop into forms where the mediator is actually inaccessible.

Similarly, the Germanic naming of pitches (with B and H as well as

the suffix-inflected Fis for F# and Es for Eb) is self-evident

neither for the Romance-language terms for pitches, which are based

on do-re-mi and modified by idiosyncratic words for "sharp"

and "flat," nor for the Anglo-Saxon scale lettered A-B-C-D-E-F-G. As

a consequence, it is a matter of learned convention, and thus of the

"joy of literacy," if lovers of Western music across language

barriers recognize that A-Eb-C-B stands for Arnold SCHoenberg (on the

basis of the Germanic spelling of the letters as A-S-C-H.)

Conversely, composers using musical tropes

to represent

non-musical objects and concepts employ a great variety of mimetic,

descriptive, suggestive, allusive, and symbolic means. Single

components (motifs or musical formulas) and their syntactic

organization, vertical texture and horizontal structure, tonal

organization and timbral coloring are entrusted with suggesting

depiction. Quotations of pre-existing musical material may add

allusive reference, and allow for modifications of context, medium,

or tonal environment that successfully express defamiliarization or

irony. Last but by no means least, countable units--from notes to

beats, bars, or sections --invite play with numerical symbols both

traditional and innovative. These latter cases move ever further into

the realm described by the phrase "the joy of literacy": not only do

such significations remain hidden to the uninitiated, we no longer

expect them to be accessible even to insiders through the means of

primary sensory perception, but only to skilled readers of the

score.

Furthermore, music, as I hope to show

convincingly, is capable of

a kind of descriptive effect that Wendy Steiner, writing about the

poetry of e.e.cummings and others, refers to as the "embodying of the

still-movement paradox." Even more than language, music can do so

without compromising its intrinsic logic. The reason for this greater

flexibility is that music, while resembling verbal texts in that it

develops in time, at the same time "paints." Like the media of visual

art, it conveys to its audience the sensual experience of

colors and textures, rather than referring to them as language

does. Both its range of register and its compositional textures

(polyphony above all) create a spatiality to which literary modes can

only allude.

6 Instrumental Music and Narrativity

But can non-texted music also narrate? In

his work on Mahler,

Anthony Newcomb (drawing on definitions by Paul Ricoeur) maintains

that it can and does. Following a work of music entails, he believes,

the same basic activity as following a story: the interpretation of a

succession of events as a meaningful configuration. Carolyn Abbate

urges us to differentiate the nineteenth-century claim that certain

linear elements of music can be regarded in analogy to the events in

a dramatic plot (music is perceived as generating expectations on the

basis of culturally established paradigms; it moves through tension

and release towards closure). She argues that music should be "seen

not merely as "acting out" or "representing" events as if it were a

sort of unscrolling and noisy tapestry that mimes actions not

visually but sonically, but also as occasionally respeaking an object

in a morally distancing act of narration."(FN10)

However, she cautions, such "moments of diegesis" are far from normal

or universal in non-texted instrumental music. Since Abbate is here

referring to music that does not, by its title, claim to be a

representation of an extra-musical reality, the allowance for

"narrative acts of music" is extremely encouraging. Non-texted music

may not be able to differentiate the details of a plotline because it

cannot establish the non-musical specifications of the characters and

props in the fictional world. But as the aesthetician Kendall Walton

in his work on the representational qualities of music confirms, mere

titles often suffice to provide this essential factual skeleton and

make music patently representational--and even narrative.

Having thus argued that music, like art and

literature, is capable

of depicting and referring to things, including things in a world

outside its own sonic realm, and that what is represented in a

pictorial, literary, or musical medium may be image or story, design

or narrative, I now turn to the more specific question how music may

represent something that does not belong to the primary reality "in

the world out there" or "in the soul in here," but has previously

been represented in a work of visual art or literature.

This leads me to a question that, I hope,

addresses the

delineation and definition of what the musical equivalent to

ekphrasis may be from a different perspective: the question whether

what we find in different cases can be described as poems or

paintings... and music? poems or paintings in music? or

poems or paintings into music? In this brief exploration I

wish to address the question how a poetic or pictorial source text

relates to--and possibly makes its way into--a musical

composition.

In order to develop pertinent categories

that may help me,

generally, to deal with the musical material in a systematic way and,

specifically, to know what to exclude and why, I turn (as I do so

often these days) to the already established methodologies in

(literary) ekphrasis.

7 Variations of Artistic Interaction

In this context, the thoughts of the

Scandinavian interarts

researcher Hans Lund, as far as we can glean them from the only work

of his that has been translated into English, Text as Picture:

Studies in the Literary Transformation of Pictures (Swedish 1982,

English 1992) prove exceedingly helpful. In his chapter "The Picture

in the Poem: A Theoretical Discussion," Lund offers a very useful

scheme of defining what stance the author of the secondary

representation (here, a poet; in our case, a composer) may be

adopting towards the work of art (here, a painting; in our case, a

painting/poem/drama) that constitutes the primary representation of

the scene or story. Lund establishes three main categories for the

relation of text to picture: combination, integration, and

transformation. (In my discussion of the equivalents in music's

relationship to the sister arts, I will further differentiate within

two of them.) Here are Lund's definitions one by one, and my own

adaptations for the field of music.

(a) Literature or Painting ... and Music

|

By combination I mean a coexistence, at best a

cooperation between words and pictures. It is, then, a question of a

bi-medial communication, where the media are intended to add to and

comment on each other. The old emblematic writing belongs to this

category. Here, too, are found certain works by authors traditionally

called "Doppelbegabungen" by German critics, i.e. authors who combine

and to a certain degree master the literary as well as the pictorial

medium. Examples are William Blake, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and

Günter Grass. Works which are the results of a creative

cooperation between a writer and a pictorial artist [...] are also

found here. Illustrations made afterwards to match literary texts are

not primarily a concern for literary scholars but for art historians.

|

What Lund is sketching here amounts, it

seems to me, to two

somewhat different genres in the case of musical composition: setting

and collaboration; both answer the questions put in the heading of

this chapter with "Poems or paintings and music."

Collaborations involving music as one of the key components include

works like Parade (by Cocteau + Satie

+ Massine + Picasso)

and L'histoire du soldat (Stravinsky +

Ramuz), to name only two outstanding cases here.

Collaborations with music as one component differ essentially from

transformations of a painting or poem into music, whereby a

structured entity with all its constituent parts and many layers of

message is recreated on another plane. They are excluded from this

study for two reasons. First, it is usually unclear which sign

system, if indeed any of those involved, should be considered

primary, and which constitutes the transposition. Second, one may

assume that the myriad aspects of communication, which would

otherwise be expressed within a single artistic text, are conceived

as being shared among the collaborating arts here. We are, then, not

dealing with the transformation of form and content from one artistic

representation into another, but instead with a sort of "synthetic

effect" whereby the various arts contribute the constituent parts of

a single artistic gestalt and message. In such a joint venture,

individual components complement one another but could often not

stand on their own.

Music knows few cases that correspond

directly to the phenomena of

"emblematic writing"; or the dual art work of "Doppelbegabungen." A

composer like Arnold Schoenberg, who was also a gifted artist,

nevertheless did not, to my knowledge, create any work in which

expressions of his dual talent combine in such a way as to engender a

single overarching artistic message. The closest analog in recent

music is probably Erik Satie. Many of his piano scores (see, e.g.,

Sports et Divertissements, published as facsimile) tread

a

fine line between musical score and artwork. The brief pieces are

prefaced with drawings by Charles Martin and may have been intended,

or so Satie scholars believe, to be looked at as much as performed.

From the time when emblematic writing itself blossomed, one

composition at least seems to function as a musical analog. In the

early 17th century, Michael Maier created a work under the title

Atalanta fugiens which consists of fifty musical

settings in

an imitative style accompanied by emblems and epigrams. (Also known

as "Michael Maier's alchemical emblem book," the work is specifically

intended to be appreciated "per oculis et intellectui").(FN11)

On the other hand, the field of music

encompasses compositions

that are manifestations of a combination of talents that is much

rarer than the dual aptitude for poetry and painting, composition and

painting, or music and poetry writing: synaesthesia. In

correspondence with some painters who claim to be putting on canvas

the hues communicated to them in musical sounds, composers endowed

with this gift of seeing colors when hearing pitches or chords may

purport to be creating a composition consisting of sound and color.

In the case of composers who, like Olivier Messiaen, expected his

audience to see with their inner eye the hues expressed in his

chords, the visual component is, for most of us, beyond our

perceptive abilities and thus beyond verification; these works thus

do not literally involve two media. The composer's assertion refers

to a very private reality which is not easily shared with an audience

and the details of which have to be taken at face value. In

compositions like Alexander Scriabin's Prometheus by contrast,

notated for clavier à lumières in addition to

the instruments of musical performance, the audience does enjoy a

bi-medial performance. Moreover, analysis reveals that the

correlations of sounds and colors are part of a complex system of

spiritual symbolism.

Settings of one text in another medium,

while often intriguing in

themselves, also constitute a hybrid form in comparison to the

phenomenon I am studying here. Whenever a poetic text is set as vocal

music, or a dramatic text as opera (or, for that matter, a musical

composition as ballet), the original medium is inflected

rather than transformed. Granted, in vocal music,

intonation--one of the many features of vocal language--is modified;

secondary features dependent upon or related to intonation, like

speech tempo, word spacing, etc., may be more or less effected, and

structure may occasionally be expanded by repetitions. All other

aspects of the original text, however--vocabulary and syntax,

metaphors and allusions, the mode of expression and the objects

spoken of--will characteristically remain completely untouched. The

instrumental accompaniment may be anything from servant to partner

(and, in recent times, even competitor) to the vocal part, but it is

not typically entrusted with creating a self-contained musical

transformation of as many aspects of the poetic model as possible.

Rather, we often speak of it as "supporting" the vocal line or

"painting a backdrop" for it. Such accompaniment acts as a musical

illustration of and to the poetic text. The case is somewhat

more complex when a choreographer chooses a piece of music to which

to compose a ballet. One would want to distinguish in what cases the

music is used primarily as an aesthetically satisfying vehicle for

the choreography, and in what cases it actually inspires a conceptual

interpretation.

Ideally, in order to make such a distinction

with authority, one

would need to create an artificial situation in which one could focus

on choreographies in a silent performance--as, for instance, on video

recordings without tone. The question would then be whether such a

purely kinetic work could be intuited as a transformation of

(essential aspects of) the musical compositions in any of the myriad

ways in which ekphrastic poems--often read without the model being

present--relate to the works of visual art to which they owe their

being. This brings me back to Lund and his second definition.

(b) Literature or Painting ... in Music

|

The second sector of my field of research I call integration.

Here a pictorial element is a part of the visual shape of a literary

work. Whereas pictorial elements in a combination have relatively

independent functions, a pictorial element in an integration cannot be

removed without destroying the verbal structure. Integration means that

verbal and visual elements constitute an overall unity which is not

reducible to the sum of the constituting elements. In this sector we

find stanzas in the shape of a goblet or hour-glass and the like in the

pattern poems of baroque poetry, as well as Apollinaire's Calligrammes

and the concrete poetry of Modernism.

|

The integration of verbal and visual

expressions into musical

compositions includes many examples that need little reflection:

neither verbal performance instructions nor the visual element of the

musical notation itself would normally prompt us to think that we are

dealing with a relationship between two art forms, although both

instances meet the condition: both will not be encountered

independently of the musical contents. Musical notation would not be

in existence without the medium it aims to perpetuate, and

compositions would not have survived --or at least not in a condition

as close to their original design--without the help of some means of

record-keeping. Similarly, performance indications detached from the

music to be performed make no sense, while music conceived with

expressive nuances that cannot be specified unequivocally outside the

verbal medium loses a valuable dimension when deprived of these

directions.

While these examples of integration hardly

concern us in the

context I have set out to examine here, there are several other cases

that would require answering our initial question with "the visual or

the verbal in music." Music knows the equivalent to "stanzas

in the shape of a goblet."(FN12) Conversely,

Kurt Schwitters's famous Ursonate and many works of Hugo Ball

have shown us that "poems in the form of musical sound patterns" are

equally possible. Then there are cases in which visual elements that

originate outside music appear integrated into a piece of music. One

example occurs in scores whose visual presentation follows shapes the

outlines of which suggest depicted objects.(FN13)

In other cases, a constituent part of the musical language is based

on a linguistic component which would not necessarily appear

independently in a poem or drama; themes shaped on the basis of

letter-name allusions (B-A-C-H etc.) fall into this category.

Finally, as if in combination of the implicit graphic aspect and the

implicit letter names, a musical score may contain elements that are

graphically both musical and verbal text. The most striking

example that comes to my mind is the title page of a composition for

male chorus written in the ghetto Terezín by one of its

inmates, the composer Pavel Haas. Besides the title itself, Al

Sifod, and the usual information regarding composer, poet--Jakov

Simoni--and scoring, Haas decorates the title page with musical notes

that, while they are carefully placed on their staves, are actually

adapted to look like Hebrew letters. The power that be in the camp

would hardly have recognized this, but the ones for whom the message

was intended did: it reads "Kizkeret lejon hasana harison vemuacharon

begalut Terezín"--In remembrance of the first and at the same

time the last anniversary of the Terezín exile.)(FN14)

One step further, musical scores may be

accompanied by verbal and

visual texts in the form of epigrams and illustrations. Since

epigrams are frequently quotations from extant literary works, they

could, of course, stand alone and do not concern us here.

Illustrations in musical manuscripts, however, form a category of

their own. Before Satie's sketches in his own pieces at the beginning

of our century, they were known primarily from manuscripts of late

medieval and Renaissance music. An illustrative example is the famous

Chansonnier Cordiforme, the "heart-shaped chansonnier." More fanciful

than useful for music making, it is a kind of troubadour song written

into a preciously illuminated heart (topped with four instead of two

semicircles). Similarly, the visual, verbal, and musical components

appear almost inseparably integrated, and the artistic ingeniously

blended with the practical, in the manuscript pages of

fifteenth-century canons.

In a four-part untexted canon by Bartolom‚

Ramos de Pareja

(c1440-1491), the single staff containing the musical sequence is

bent into a circular shape and set, in golden ink, against a

background of deep sky blue. Wind spirits blowing from the four sides

of the page into the notes indicate the entry of the four voices,

while the calligraphy fitted into the circle betrays the composer as

a music theorist, who informs singers about the modes they will

detect in the four-part harmony resulting from the proper execution

of this canon.

Opera as a genre typically relies on

integrating a verbal text

into the composition in such a way that both elements, lyrics and

music, when represented separately, seem to be lacking an essential

complement. However, the degree to which the component parts of

opera--the libretto on the one hand and the "pure" music on the

other&--are capable of also functioning independently is often

greater than in the cases Lund mentions. While the hour-glass shape

of a poem is really nothing but an empty line drawing (and usually a

fuzzy one, for that matter) once the words are taken out, the same

cannot be said for librettos. Many of them may be of the rather more

unimaginative kind when taken as dramatic works; but, as testified in

the now established term "Literaturoper," there are a number of

literary works that originated as dramas and continue to stand as

such, before and after they are used by a composer. And as, for

instance, Hindemith's symphonies Mathis der Maler and Die

Harmonie der Welt prove, even the music can sometimes function as

a fully valid artistic testimony when taken on its own. Yet these

cases are exceptions rather than the rule, and the "music alone" or

"drama alone" typically differs from the corresponding component that

forms a constituent part of the opera.

This brings me to Lund's third definition.

(c) Literature or Painting ... into Music

|

In the third category--which I call transformation--no

pictorial element is combined with or integrated into the verbal text.

The text refers to an element or a combination of elements in pictures

not present before the reader's eyes. The information to the reader

about the picture is given exclusively by the verbal language.

|

This, then, is the case of a poem or

painting being

transformed into music--the focus of this study. Where

transformations appear in poetry or prose on painting,

they

are referred to as ekphrasis. In music, such ekphrasis can take as

its object a work of literature (as is the case in Ravel's piano

piece Gibet, briefly described above) or a work of visual art.

Compositions that deal respectively with these two sides of musical

ekphrasis include, on the one hand, symphonic compositions on

Symbolist drama (Charles Martin Loeffler's and Bohuslav Martinu's

compositions on Maurice Maeterlinck's marionette play La mort de

Tintagiles, and Schoenberg's work on Maeterlinck's Pelleas und

Melisande) as well as musical works about poems short and long

(Schoenberg's sextet Verklärte Nacht and Elliott Carter's

transmedialization, in Concerto for Orchestra, of

Saint-John-Perse's epic poem Vents, and to a lesser degree, in

A Symphony for Three Orchestras, on Hart Crane's epos The

Bridge.(FN15) On the other hand, I

explore music on paintings: the musical "triptychs" twentieth-century

composers form from works of quattrocento artists (Ottorino

Respighi's Trittico botticelliano and Bohuslav Martinu's

Les Fresques de Piero della Francesca), two

transmedializations of a Romantic painting (Serge Rachmaninov and Max

Reger on Böcklin's Isle of the Dead), three musical

ekphrases of the same early modern work by Paul Klee (the English

composer Peter Maxwell Davies's, the American Gunther Schuller's, and

the German Giselher Klebe's compositions under the title The

Twittering Machine), and two contemporary Danish composers'

reactions to drawings by M.C. Escher (Per Norgard's Ant Fugue

from Prelude and Ant Fugue [with Crab Canon]: Hommage a

M.C. Escher and Hans Abraham's Three Worlds).

When transformation of a work of visual art

is brought onto the

theatrical stage and wedded with the miming aspect of that genre, we

speak of enactments. Here I know of at least three

compositions based on serial paintings that can be shown to contain

distinct elements of enactment. This is particularly intriguing given

the fact that neither composition is strictly theatrical in its

focus. Music knows a few cases where something corresponding to the

typical dual transformation--from the visual to the verbal to the

mimed--occurs outside the opera. However, since the operatic

environment is the characteristic one for this sub-genre, I would

like to introduce musical enactment using as an example the three

scenes from act VI ("Sechstes Bild") of Hindemith's opera Mathis

der Maler.

In the first of these scenes, Hindemith's

painter Mathis attempts

to soothe the distraught young girl Regina with a narration of what

he claims to see in a picture portraying three angels. His verbal

depiction leads us to one of the second-tier panels of the

Isenheim Altarpiece, the masterpiece of the operatic

protagonist's historical model, Grünewald. At this juncture,

Hindemith the librettist puts into the mouth of his character Mathis

a most intriguing tripartite description and interpretation of the

panel that the historical "Master Mathis" painted ten or more years

prior to the year into which this fictional conversation is placed.

In the way in which Mathis tells Regina about the "pious pictures,"

no mention is made of who created them; the narration appears guided

by the idea and intention of what is portrayed rather than by an

attempt to describe the visual composition in all its details. Mathis

focuses on the spiritual aspect of this concert--and so does the

music in which Hindemith sets this scene.

This "narrated portrayal" of the "Angelic

Concert" is complemented

in the scene that follows by an enactment combined with a narration

of one of the two rear panels, "The Temptation of Saint Antony." The

events presented on stage function on three levels. First, in the

larger context of the operatic plot, Mathis's encounter with human

tempters and monstrous tormentors appears like a bad dream--or a

vision, given that he perceives himself as the Egyptian hermit

Antony. Second, the verbal onslaught by the seven human tempters

functions as a multi-layered interpretative embodiment of what is,

beyond the reference to the pictorial representation in the altar

panel, both the inner story of the temptations of Saint Antony and a

dramatic portrayal of the plight in which Mathis is caught. Third,

the physical attack by the monsters is at the same time a tableau

vivant of Grünewald's depiction and its musical

transmedialization: the choir does not only accompany with insults

and spiteful interpretations the assault by hellish monsters to which

Mathis/Antony is subjected in the center of the stage, but

simultaneously narrates the scene as painted by Grünewald. All

images evoked in this scene also reflect a deeper spiritual meaning

since they can be understood as provocations, as torments that emerge

from the victim's own doubting mind. They represent his spiritual

nightmares and the internal enemies that haunt his soul.

The third scene in this sequence, entitled

"The Visit of Saint

Antony in the Hermitage of Saint Paul" after the Grünewald panel

to which it relates, limits the enactment to the visual recreation:

stage design, costumes, posture and position of the two actors. No

narrative relates what we see and hear to the painting, thus allowing

us to focus all the more on the symbolic significance of the

scene.

The older hermit Paul ("embodied" by the

operatic character,

Cardinal Albrecht) acts as a spiritual adviser to Antony

(= Mathis). While his verbal admonitions deal

unequivocally with the reality of the artist in the time of the

Lutheran Uprising and the Peasants' War, the scenic setting binds the

conversation into the larger conflict of conscience that is, both

literally and figuratively, through the ekphrasis of the altar

panels, the subject matter of the opera. Hindemith's music adds a

wealth of nuances that corroborate and enhance this interpretive

layering.

Another fascinating case of such mediated

enactment of a pictorial

narrative exists in Stravinsky's opera The Rake's Progress.

The stimulus here is a series of eight engravings etched in 1735 by

William Hogarth, after an equal number of paintings he had completed

a year earlier. Stravinsky, inspired by these prints, followed Aldous

Huxley's recommendation to ask Auden for a libretto dramatizing the

story told in the etchings, on which he could then base his opera.

Auden accepted and, with the help of Chester Kallman, told the story

of the rake in a style that aimed at once (I quote Williard

Spiegelman) "to recapture the myths and language of an earlier, more

optimistic world, and to examine that world from the perspective of

our own.... the libretto is Auden's attempt to adapt certain poetic

styles to the conditions of twentieth-century literary life, to

imitate or parody older models in much the same way that Stravinsky's

music casts new light on earlier operatic techniques."

However, what sets this case of musical

enactment of a pictorial

source apart from the two texted examples I will be examining as part

of my study is the fact that the Auden/Kallman libretto is a literary

ekphrasis in itself, of which Stravinsky's music then gives a

setting. By contrast, the texts Honegger uses for his oratorio La

danse des mort on Holbeinis Totentanz, while "authored" by

Paul Claudel, are actually compiled from the Bible. As such they

constitute something akin to a verbal embodiment of the common source

that inspired the artist and the composer, rather than Claudel's

ekphrastic reaction to Holbein's artistic rendering. The situation is

very similar in the case of Janacek's composition on Josef

Kresz-Mecina's panels The Lord's Prayer which the composer

based on five tableaux vivants he had devised himself. Here,

too, the text predates both the art and its musical

transmedialization.

Compositions based on ekphrastic

poems--poems that are themselves

transformations of pictorial texts--while often charming, are least

pertinent to the aims of my study. They are usually little more than

mere settings. Francis Poulenc's songs on Guillaume Apollinaire's

Le bestiaire, whose poems are in turn based on woodcuts

by

Raoul Dufy, fall into this category. So do Poulenc's settings of Paul

Éluard's poems Travail du peintre, which verbally

represent the style and characteristics of various contemporary

painters, and Reynaldo Hahn's similarly motivated Portraits de

peintres after poems by Marcel Proust. Poulenc also set

Apollinaire's Calligrammes, which are not "poems on pictures"

but rather "poems in the form of pictures"--a feature that is by

necessity lost once the text, now used as "lyrics" for songs, is

fitted between the staves of musical notation. At the other end of

the spectrum, verbal ekphrasis may indeed stimulate further musical

ekphrasis in an independent musical work. Thus Debussy's piano piece

Clair de lune in Suite Bergamasque was

apparently

inspired by Paul Verlaine's ekphrastic poem (by the same title) after

Antoine Watteau's painting, Fêtes galantes.

Finally, the composer's interest in a

musical transformation of a

given work of verbal or pictorial art may inspire a creative artist

working in yet another medium to expand the ekphrastic process even

further, adding yet another transformation. The cases of dual

transmedialization I am most eager to examine are those involving

three different media each: from the pictorial to the verbal

and on to the musical, from the pictorial to the kinetic on to the

musical, or from the poetic model to the musical transformation to

the visual or kinetic interpretation. Detailed analyses exploring two

examples for this kind of multimedial "fate" in interarts space of an

original work will conclude my case studies.

8 Central Questions in Research on

Musical

Ekphrasis

The central questions I will be asking

regard the scope and nature

of this interartistic, intersemiotic transmedialization and can be

summed up as follows:

|

*

|

What choices do individual composers make in their

quest musically to transmedialize a pictorial or literary

representation?

|

|

*

|

Do the choices made by the composers of a certain

historical and cultural context allow to distinguish and describe a

newly emerging "convention" of intersemiotic transformation?

|

|

*

|

Does the range of stances adopted by composers to

works of literature or visual art parallel those observed in ekphrastic

poets?

|